Basle Beginnings

From Switzerland to the South Pacific, from Bali to Thailand, Theo Meier's life was as varied and exotic as his artistic output, his character as colourful as the oils with which he painted.

Born in 1908 in Basle Switzerland, Meier, like the city in which he grew up, was fortunate to avoid the hardships of war which quickly overtook much of Europe. Following in his father's footsteps, he underwent a commercial apprenticeship. At the same time, he attended the Basle School of Art, and enjoyed late night discussions with the local painters, an experience which proved fertile to the young painter.

At the age of twenty, with the assistance of a scholarship form the School of Art, Meier embarked on an independent existence as an artist. He established his residence in Spalenvorstadt and survived on "sausages, salt rolls, cheap Spanish red wine, and hope".

The Early Days

A commission to paint a portrait by the University of Basle gave Meier his first break. The sitter, Jacob Schaffner, was so pleased with the result that Meier, as well as his fee, was given recommendations to various other famous people, including Max Liebermann, Karl Hofer and Otto Dix.

On the basis of these recommendations, Meier travelled first to Berlin, where he met Liebermann and Hofer at the Berlin Academy, and also Emil Nolde, one of the contemporary painters he most admired.

After Berlin, Meier moved on to Dresden, where his meeting with Otto Dix, at that time lecturing at the Dresden Academy, was perhaps of more lasting significance. In Meier's own words:

I learned more of the mechanics of painting during my brief stay in Dresden than ever before. Dix taught me to draw and the simple things that I have at my finger-tips like grounding and the mixing and application of colours so as to bring out the luminosity.

On his return to Basle, Meier, through his acquaintance with Paul Sacher, founder of the Basle Chamber Orchestra, met and painted the musicians Arthur Honegger and Igor Stravinsky. The results were striking achievements, capturing the essence of these distinctive creative personalities.

To the South Pacific

In his early days, Meier had enjoyed the writings of his fellow countryman Jean Jacques Rousseau. Similarly he had been struck by the primitivism of Gaugin's paintings at an exhibition in Basle. As he recalls: "I was carried away into another world... At the sight of Gaugin's paintings, I suspected that something existed there with which a painter must instinctively feel himself at home".

Meier embarked on his own South Pacific journey at the age of 24. To finance the voyage, he founded a club, in which every member pledged a monthly sum, in return for which they could choose one of Meier's paintings on his return.

By these unconventional means, Meier was able to sail to Papeete by way of Guadeloupe, Martinique and the Panama Canal. In Tahiti, Meier certainly discovered the beauty--both in the colours of tropical nature and the local women--that had been Gaugin's inspiration. However, the primitive simplicity that characterises Gaugin's work was little in evidence, and, concluded Meier, was probably always more part of the artist's fantasy than reality.

Meier returned to Basle, with his roll of paintings, "including painted coffee-sacks, [which] went through the customs as Carnival decorations for six francs".

Despite the sense of disappointment which resulted from the trip, Meier had also come to an understanding which would shape his future life and work:

I became aware after my return of something new in Basle--how a community cultivated the arts within its walls. Splendid concerts were to be heard, and the city created an Arts Fund for paintings, mosaics, and sculptures in squares and on walls wherever it was appropriate. A painter was something of a cultural phenomenon--and there were many of them. That was not what I was looking for. I had in mind a country in which the painter lived, as one might say, unobserved but belonged in his activity to the whole. Perhaps I had also hoped to find a country where the painter was shaped by the power of its culture.

Unlike his predecessors, Nolde and Pechstein, who nearly twenty years earlier had made their South Pacific journeys and returned enriched with new material and themes yet essentially unchanged, Meier's first encounter with the tropics had been a fundamentally transforming one.

To Bali, the Morning of the World

A year later, Meier was travelling again. After a brief stay in Singapore, he arrived in Bali where " the delirium laid hold of me which even today has not subsided".

At that time, Bali was still very traditional, a place where people lived according to ancient belief systems in a society little impacted by the modern world. Meier found in Bali, amid the luscious tropical scenery and beautiful women, the culture that had been missing in Tahiti. The contrast was striking:

When I arrived in Tahiti, I was very disappointed that the culture I had dreamed about no longer existed there, but I did observe the components that Gaugin had used to build up his beautiful paintings. He showed me tropical Nature, and this influenced me so enormously that I began looking for a place where perhaps more culture had survived, but in the same natural setting. That place was Bali. There I was shaped, and became what I am today.

Meier first took up residence in Sanur on the south of the island, where he immediately found inspiration: "I had no need to invent settings for my compositions. I saw them continually before me, in the temples and daily life". He cultivated friendships with other artists in Bali, including the German painter Walter Spiess, whose bamboo dwelling in Iseh he would later make his own. Before long, Meier was inextricably part of the cultural and artistic life of the island, visited by celebrities and politicians alike.

In 1936 Meier married his first Balinese wife, a relationship which lasted until 1941. A year later, times changed dramatically when the Japanese arrived in Bali. They landed in Sanur, where Meier was living, at which point he fled to Saba.

As a citizen of a neutral country, Meier received permission to stay in Bali (unlike his friend Walter Spiess who met his death aboard a prisoner of war ship crossing the Indian Ocean). Unfortunately, though, many of his paintings were lost:

The greater part of my artistic harvest of six joyfully creative years, some sixty pictures, found unlooked-for utilization. Those pictures in which naked women were portrayed found their way to Japanese warships, and now rest, I suppose, at the bottom of the ocean. The Japanese used other pictures as covers for gaming tables, used them to light fires, or as sunshades. Balinese accepted a few as payment for services rendered. I later received some of these back.

Meier married another Balinese girl, Madé Pergi, subject of some of his most striking portraits, and life continued. Japanese defeat in 1945 was followed by the onset of Indonesia's long war for independence, Bali never quite returning to it's pre-war innocence. Nevertheless, Meier continued to paint his cherished island, finding fortune in the temperament of Indonesia's first president, Sukarno:

Luckily for the painters, he was a friend of the fine arts. I also had the fortune to receive handsome commissions from him. His visits to me were great events for the village of Iseh. In his company I met Nasser and Nehru who described Bali most poetically as "the morning of the world".

In 1948, Meier's wife Madé Pergi gave birth to a daughter. However, a few years later, the couple parted, on amicable terms.

To Thailand

After 15 years in Southeast Asia, Meier returned to Switzerland for a year in 1955, but soon longed for the warmer climate of

his adopted home. He returned to Bali briefly, but in 1957 travelled to Thailand on the invitation of his friend Prince Sanidh Rangsit. Residing in the Prince's summer home on the beach at Hua Hin, he met his last wife, Laiad.

In 1961 Meier moved to Chiang Mai, Northern Thailand, where he set up home with Laiad in a beautiful teak house on the banks of the River Ping. As in Bali, he entertained a great variety of guests passing through the region, his delight and expertise in cultural and culinary matters almost as legendary as his artistic output.

Meier continued to paint in the tranquility of his Northern Thai home until his demise in 1982. His prolific opus outlives him in galleries and private collections across the world, testimony to a joyfully and harmoniously lived life. For it is not so much the exotic in itself that lends Meier's work it's magical quality, but rather the warmth and understanding the artist infused into each of his subjects. This is paradise viewed from within, not without.

|

|

| At night we wandered about the city and painted, by the chilly lights of gas-lamps, vast nightscapes with heavy, warm shadows of trees. The laws of chiaruscuro were a revelation to me and later a nightmare. Similarly with the play of warm and cold shades. I'm still not finished with the complementary effects of colours. |

|

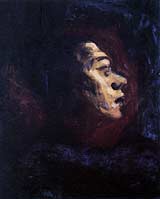

Self Portrait, circa 1928

|

| I have always been better able to paint people in whom I perceived a vital strength rather than refined types. Once I painted a banker, and when his wife saw the picture she was horrified! 'He looks just like a master-butcher!' and that is more or less how he had struck me. |

|

Landscape in Morea

Painted on a rice sack in 1933

|

| I had in mind a country in which the painter lived, as one might say, unobserved but belonged in his activity to the whole. Perhaps I had also hoped to find a country where the painter was shaped by the power of its culture. |

|

Self Portrait, 1946

|

| I concerned myself very closely in Bali and, indeed, elsewhere with ethnological details and relationships. For instance, if I had not studied thoroughly the music of the slunding orchestra, I would probably not have managed to portray a rejang dnace so realistically. |

|

Self Portrait, circa 1956

|

The Tropics--what an expression that is! Everything is contained in it--as if in entity--the people, the scenery, the culture. In the Tropics, everything is simpler, bigger, and more evident. The contrasts are, in many respects, more delicate...

In the Tropics, one thing flows into another. The outlines dissolve. |

|

|